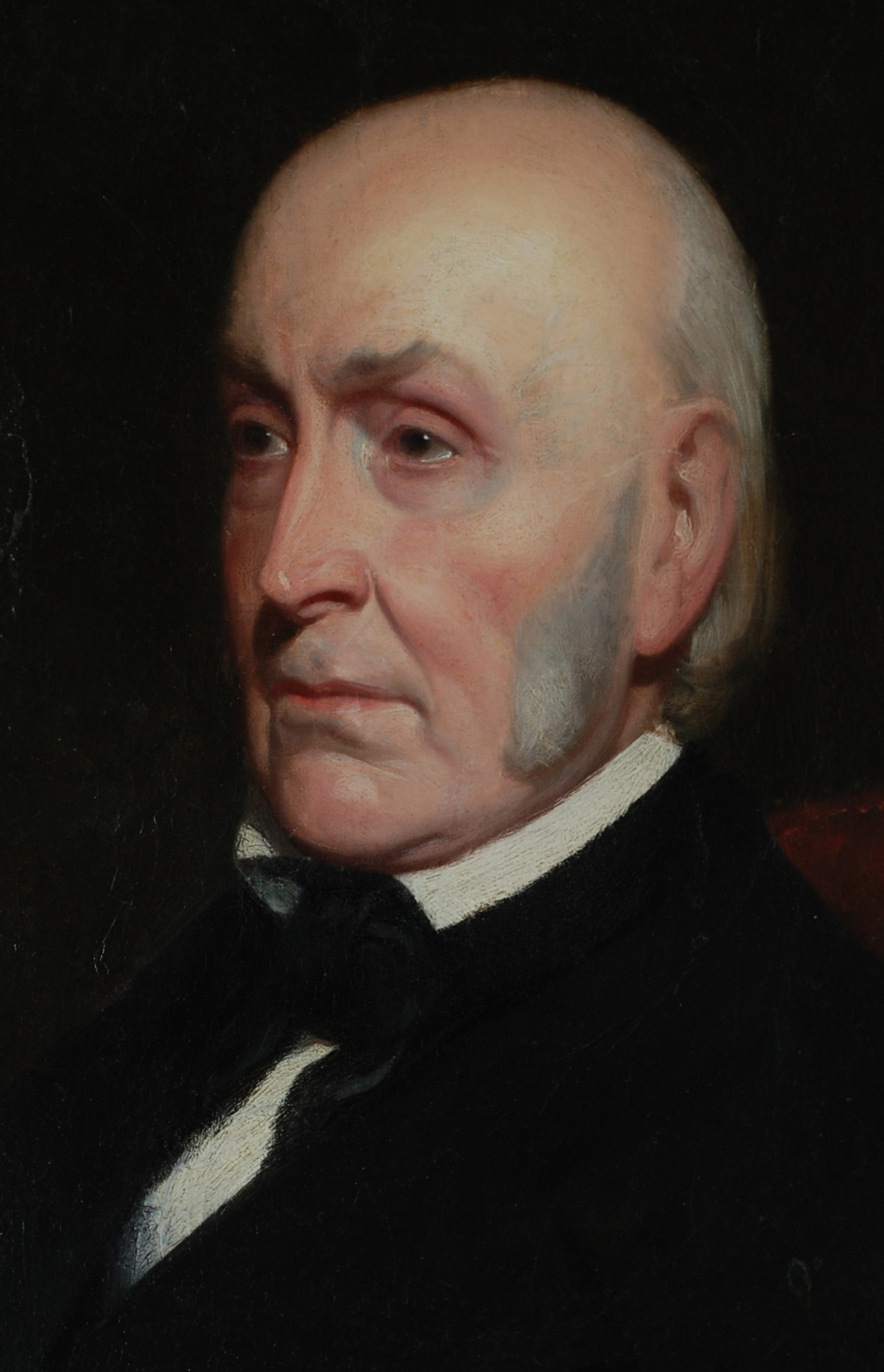

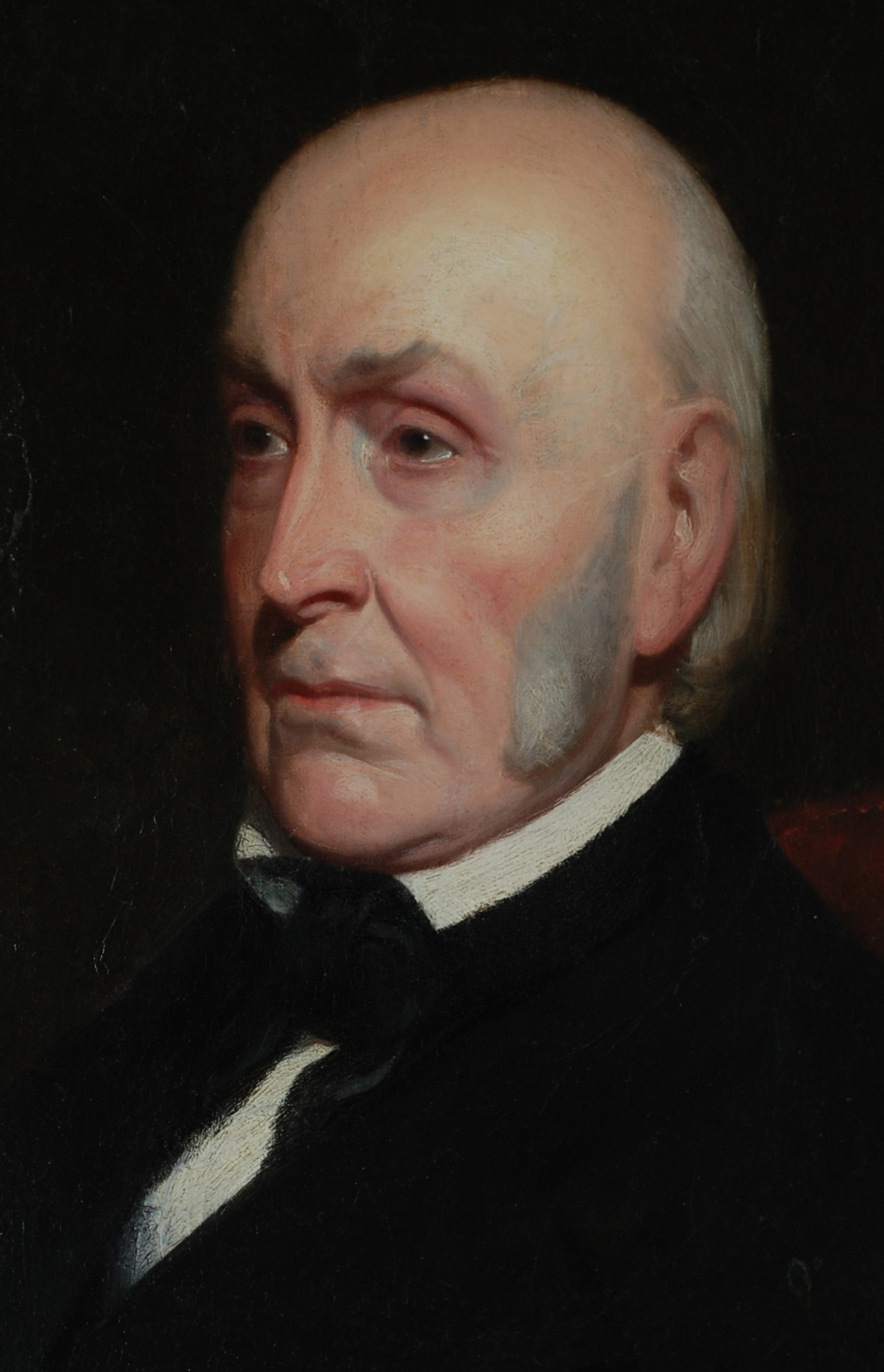

John Quincy Adams’ Role in American Astronomy

By John E. Ventre, Historian for the Cincinnati Observatory

2014 February

2014 February

Following his stint in the Senate from 1803-1808 and serving as a professor at Harvard University, John Quincy Adams, otherwise known as JQA, was appointed as America’s first Minister to Alexander I, Czar of Russia, in 1809, where the two became fast friends. Alexander, being well schooled in astronomy, passed this knowledge onto his friend, JQA, and with this exposure he developed a passion for astronomy that he had for the rest of his life. Within the pages of his diary, JQA recorded what he observed in the sky with his unaided eye or his hand-held telescope.

While serving as Secretary of State (1817-1825) under President James Monroe, a petitioning letter was written by JQA in 1823 to the supporting members of the Harvard Corporation for a world-class observatory to be constructed at Harvard. One of responsibilities as Secretary of State, according to JQA, was to promote “learning”, which incorporated the knowledge of astronomy. His petition followed previous efforts to establish an observatory at Harvard.

In 1823 he also offered to fund a Harvard professorship in astronomy, and he pledged $1,000 “a sum more suited to my circumstances & means than to my inclination…” for the erection of an observatory at Harvard, provided that the remaining, necessary funds to complete the project could be raised within two years. The required funds were not raised, thus he renewed his generous offer in 1825. Yet again, the sufficient funds were not raised and JQA’s early efforts to establish Harvard's Observatory proved unsuccessful.

Evidently his persistent and oppressive attempt to persuade governmental support, including to the General Court of Massachusetts, for the proposed Harvard Observatory was rebuked by Congress when they created the U.S. Coast Survey. The authorizing bill specified that its funding shall not authorize the construction of a permanent astronomical observatory.

Adams was elected as America’s sixth President in 1825 and his first annual address to Congress challenged Congress to build the country’s first national observatory. The “Old Man Eloquent”, again, argued the duty and right of government to promote learning, and he emphasized that a significant component of this duty was to erect an astronomical observatory:

It is with no feeling of pride, as an American, that the remark be made, that, on the

comparatively small territorial surface of Europe, there are existing upward of one

hundred and thirty of these lighthouses of the skies; while throughout the whole

American hemispphere, there is not one.

Adams picturesquely referred to observatories as “lighthouses of the skies”, and his States-Rights political opponents constantly criticized him for his choice of this term.

After his one term presidency ended in 1829, JQA was elected to the House of Representatives in1830, where he served until he died in 1848. To this day Adams was the only former President to ever serve in the House.

During his time in the House, he perceived a need for an observatory to serve practical purposes essential to national interests, such as accurate time determination and the calibration of the Navy’s chronometers which enabled ship captains to accurately determine their longitude while at sea. JQA failed in his attempt, but his failure was predicated principally by the State-Rights movement that was in control of Congress, and they did not want to relinquish to the Federal government any monies or power.

Nevertheless, in 1830, he was partially successful in his attempt to found a national observatory when Congress authorized the establishment of the Naval Depot of Charts and Instruments. Their modest astronomical instruments included a Patten transit instrument, a 3.75-inch Troughton transit instrument, and a 3.2-inch Simms refractor telescope (transit instruments are special telescopes used for the precise observation of star positions, often as a way to determine precise time).

Other than Quincy’s 1825 attempt to found a national observatory, there had been little interest in American government sponsorship of astronomy, but in 1835, the unusual bequest of an Englishman, James Smithson, resulted in the first government foundation, the Smithsonian Institution, for the general advancement of science in America. Like John Quincy, Smithson was interested in expanding the scientific knowledge of mankind. He bequeathed his estate to a nephew, who died without an heir, thus forwarding his generous bequest (current production worker value of $ 256,000,000) was forwarded to the United States.

Congress argued over ten years as to the ultimate use of the Smithson bequest. As Chairman of the Congressional Committee to resolve the dispute over the disposition of the Smithson bequest, JQA petitioned that the bequest be utilized for a research institution: a “National Institute for the Promotion of Science and Literature” that would include a national observatory and museum. Yet, in Congress’ final debate in 1846 on the disposition of the funds JQA sarcastically stated, “I am delighted that an astronomical observatory--not perhaps so great as it should have been--has been smuggled into the number of institutions of the country, under the mark of a small depot for charts…”

JQA chaired a Harvard committee in 1840 to raise funds to convert the Dana house, a private faculty residence on the Harvard campus, into an observatory. The house was modified to incorporate a rotating wooden cupola on top of the residence, eventually to house a telescope. Evidently, as early as the 1820’s, JQA had proposed that the land upon which the Dana house stood be considered as a potential site of an observatory.

In 1842 Congress authorized the expansion of the Naval Depot of Charts and Instruments into an Observatory and by 1844 the U.S. Naval Observatory was established, when a 9.6-inch Merz and Mahler refractor telescope was acquired.

In his support for the U.S. Naval Observatory JQA wrote: “There is no richer field of science opened to the exploration of man in search of knowledge than astronomical observation; nor is there, … any duty more impressively incumbent upon all human governments than that of furnishing means and facilities and rewards to those who devote the labors of their lives to the indefatigable industry, and unceasing vigilance, and the bright intelligence indispensable to success in these pursuits.”

By the mid-1840s, the Harvard Observatory had established a Visiting Committee, headed initially by Adams, who served on the committee until his death. The committee exercised influence over the operation of the Observatory.

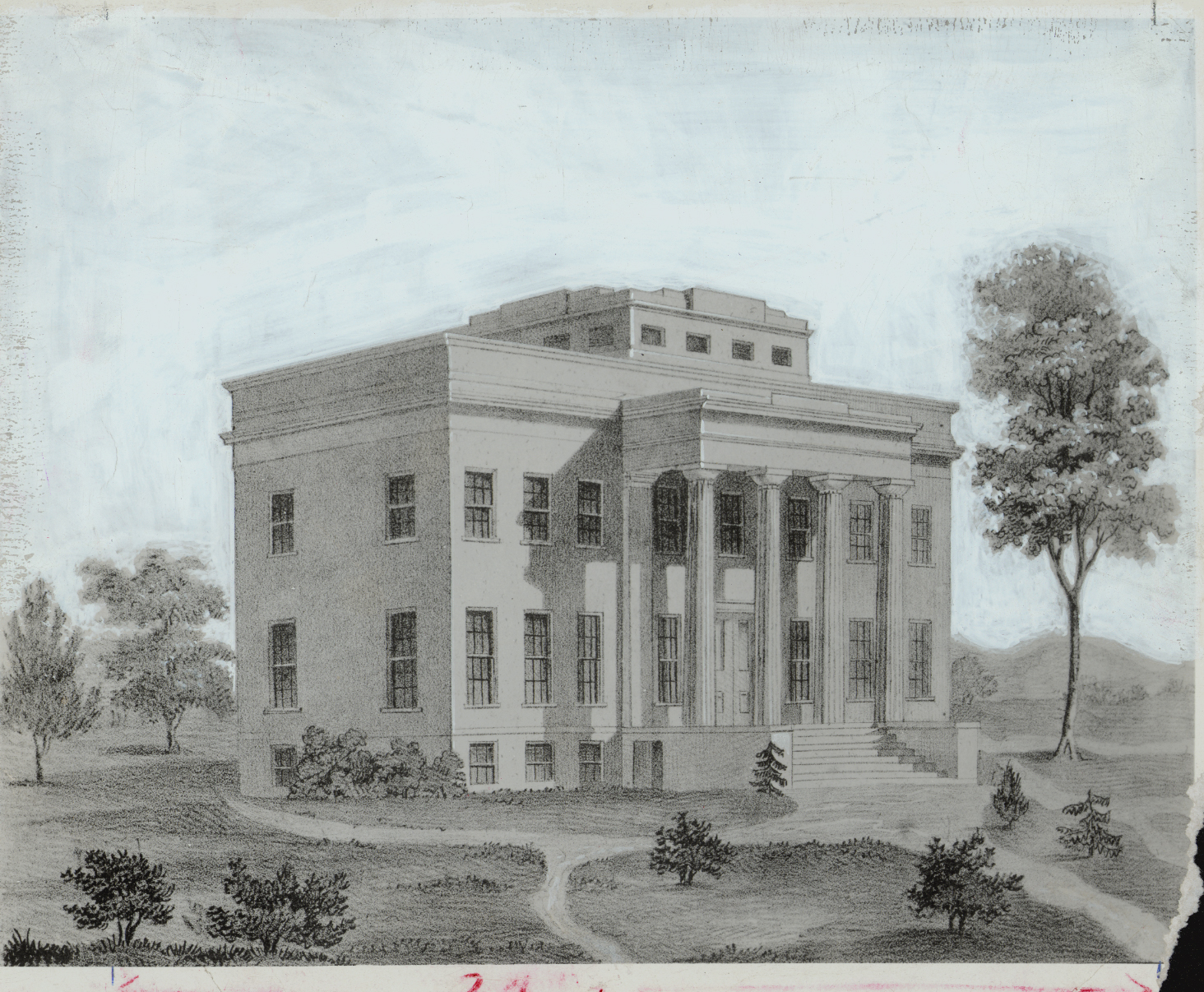

The country’s first public observatory was founded in 1842 when Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel’s dynamic public lectures aroused the citizens of Cincinnati to form the Cincinnati Astronomical Society and build the Cincinnati Observatory. They purchased the second largest telescope in the world, an 11-3/16 inch refractor, from Merz and Mahler in Munich, Bavaria that very same year. In 1843 they invited the former President to lay the corner stone of their planned observatory.

John Quincy was 76 years old and in poor health at the time. Despite his family’s pleas to ignore the invitation, especially when it required arduous travel from Boston to Cincinnati during November’s wintery chill, he accepted and wrote to Mitchel that, “he was on his way and if he was delayed it was not his fault.” The first leg of his two-week trip started with him traveling by rail from Boston to Lake Erie. The second leg transported him by steamship across the lake to Cleveland. A canal packet floated him from Cleveland to Columbus. And a stagecoach transported him from Columbus to Cincinnati for his final leg of the trip.

Why did he agree to come to Cincinnati to lay the Observatory’s corner stone? Not only did he have a passion for astronomy and wanted to support the erection of a significant lighthouse in the sky, but he was also a politician and he was driven by political opportunities. He believed the occasion to be an opportune time to exploit the city’s interest in astronomy and build support in the next session of Congress for his version of the Smithsonian Bill.

JQA never had the opportunity to view through the Cincinnati refractor telescope, but he did view through Harvard’s great refractor. He died in 1848 of a stroke on the floor of the House of Representatives.

We extend happy Presidents' Day wishes to John Quincy Adams and extend our appreciation to him for his contributions in the fostering of early American astronomy.

*** “An Oration, Delivered Before The Cincinnati Astronomical Society, on the Occasion of Laying the Corner Stone of An Astronomical Observatory, on the 10th of November, 1843” - This book, digitized by Google from the original work in the University of Michigan Library, provides correspondence preliminary to the Cincinnati Observatory Corner Stone Laying Ceremony, address of Judge Burnet, address of John Quincy Adams (which begins on page 11), and an appendix which includes the extract of an earlier address of John Quincy Adams and the Constitution of the Cincinnati Astronomical Society adopted in May of 1842. The corner stone of the Cincinnati Observatory was actually laid at the Observatory site on Mount Ida (a hill just east of today's Downtown Cincinnati), in the presence of John Quincy Adams, on November 9, 1843. However, due to heavy rain, the ceremony was delayed until the next day, November 10, 1843, when it occurred in the Wesley Chapel in Cincinnati. Following John Quincy Adams' address, Mount Ida was renamed Mount Adams in the former President's honor. This was John Quincy Adams' last public address outside of Congress. He never had the chance to return to see the completed Cincinnati Observatory, which began operation on April 14, 1845.

Source: John E. Ventre, Historian for the Cincinnati Observatory. He has taught Astronomy at the University of Cincinnati and served as the first Administrator / Director of the Cincinnati Observatory Center (the non-profit organization which now leases the Observatory from the University of Cincinnati and operates the Observatory).

References:

Dick, Steven J. Sky and Ocean Joined - The U.S. Naval Observatory 1830-2000. 2003, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Jones, Bessie Zaban and Boyd, Lyle Gifford. The Harvard College Observatory-The First Four Directorships, 1839-1919. 1971, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Also see:

Ventre, John E.

"Presidents' Day: The Astronomy President." Blog Post.

SpaceWatchtower 2014 Feb. 17.

Return to History of The Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science, Pittsburgh

Authored By

John E. Ventre

Sponsored By

Friends of the Zeiss ***

Edited by

Glenn A. Walsh

Electronic Mail: <

jqa@planetarium.cc > ***

Internet Web Site Cover Page: <

http://www.planetarium.cc >

This Internet Web Page: <

https://buhlplanetarium2.tripod.com/bio/jqa/astrorole.html >

2014 February

NEWS: Planetarium, Astronomy, Space, and Other Sciences

Other Internet Web Sites of Interest

History of The Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science, Pittsburgh

History of Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum, Chicago

Astronomer, Educator, and Telescope Maker John A. Brashear

History of Andrew Carnegie and Carnegie Libraries

Historic Duquesne Incline cable-car railway, Pittsburgh

Disclaimer Statement: This Internet Web Site is not affiliated with the

This Internet, World Wide Web Site administered by Glenn A.

Walsh.

This Internet World Wide Web page created on 2014 February 17.

You are visitor number

Cincinnati Observatory Center,

University of Cincinnati,

Andrew Carnegie Free Library,

Ninth Pennsylvania

Reserves Civil War Reenactment Group,

Henry Buhl, Jr.

Planetarium and Observatory,

The

Carnegie Science

Center,

The

Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh/Carnegie Institute,

or

The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.

Unless otherwise indicated, all pages in this web site are --

© Copyright

2014,

Glenn A. Walsh, All Rights Reserved.

Contact Web Site Administrator: <

jqa@planetarium.cc >.

Last modified: Monday, 17-Feb-2014 06:39:39 EST.

, to this web page,

since 2014 February 17.